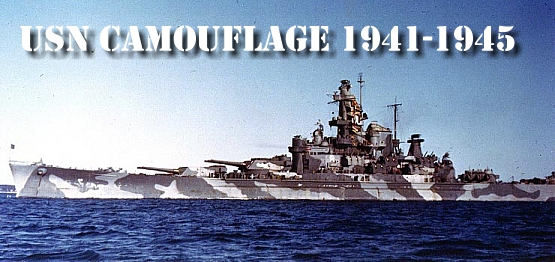

An online database of camouflage used by

United State Naval Warships during WWII

|

|

|

The

Development of Naval Camouflage 1914 - 1945 By

Alan Raven (Article reprinted courtesy of Plastic Ship Modeler Magazine issue #97/2) one

main aim, were divided into three types, Measure 31 where the average tone was

dark for use in strong sunlight, Measure 32 with the average being of medium

tone, and Measure 33, the average tone being light, for use in areas where

overcast skies prevailed. For use

with Measures 32 and 33, two new colors were added to the purple blue range.

The new colors were 5-P Pale Gray and 5-L Light Gray, both being

substantially lighter in tone than 5-H Haze Gray.

In all these measures there was extensive use of white countershading as

a way to eliminate shadows and shaded areas. These

new designs were proposed to the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets in the first months

of 1943. The personnel of the Atlantic Fleet immediately rejected the new

designs as being too conspicuous. Atlantic

Fleet vessels needed concealment over any other aspect, and anything that

compromised that requirement would not be tolerated.

Atlantic Fleet ships continued to use the well-established Measure 22. In

the Pacific, at first there was resistance to using the new measures.

Overall 5-N Navy Blue, a concealment camouflage, one that worked fairly

well against aircraft observation, was worn by almost every vessel in the fleet.

It was well liked, people believed in it, although in the 1942 batches

there had been problems with excessive fading. If left without renewal for

several weeks 5-N could fade down to a medium gray. However, in spite of the

general acceptance of solid tones in the Pacific Fleet in line with the need for

concealment, the camouflage department, working through the Bureau of Ships, did

a good job of selling Everett Warner's ideas and designs. By mid-1943 new

construction and ships refitting in the East Coast yards began to appear in the

new range of dazzle schemes. Almost every one of the initial range of patterns

employed large straight lined angular panels, leaving out curved or flowing

lines. Several of the early designs employed Measure 16 patterns using the

purple-blue range of colors. Interestingly, patterns were issued which called

for a feathered or blended edge to the panels.

While several escort carriers and landing craft wore such patterns, only

one major warship, the battleship IOWA, was so painted.

Virtually all of the 1943 designs had patterns and colors arranged in

such a way so as to create the maximum amount of course deception, almost

without regard to any other aspect. This emphasis of course made any ship so

painted extremely conspicuous, regardless of weather conditions. On many designs

the decks carried a disruptive pattern of 20B and 5-0, hoping to achieve a

degree of false heading from aerial observation. As expected this led to a

negative reaction among many in the fleet, in the same way as it had initially

done in WW I. The

camouflage section did such a good job of salesmanship that by early 1944 large

numbers of warships of all types were arriving in the Pacific showing dramatic

and multi-colored camouflage. When

complaints began to trickle back to the camouflage section from the Pacific

Fleet about the dislike of the dazzle patterns, (Saying what was needed was

concealment first, disruption second) the camouflage section countered with

scientific/come academic arguments. These exchanges continued though early and

mid-1944, at which time the camouflage section decided to send Everett Warner to

the Pacific to personally hear the views of the men, and to evaluate the

camouflage designs in their designated environment. Warner's report was delivered in September, and because it

makes such interesting and informative reading, the author has decided to quote

it in full. WARNER

REPORT 1.

The camouflage picture is still confused and while decisions are pending it may

not he proper to deal with it officially. However,

it seems to me that I should appraise you in an informal way of the trend of

events in order that you may direct the energies of the designers into useful

channels. The camouflage

requirements of each type of vessel differ so materially that it has been

thought best to deal with each type individually. Suggested research in design will be mentioned under the

various headings. CRUISERS

2.

While opinion is not united in proposed remedies the cruisers have evinced more

dissatisfaction with current camouflage than any other group.

A change in operating conditions for which they believe the present

painting measures are unsuitable seems to have brought about the situation. They

expect more and more to be seen against island backgrounds, and to he required; "to

operate close to the shores of islands for initial and covering bombardments and

for support missions. Camouflage

should offer concealment rather than type or course deception". (Ltr.

dated 7/31/44 from Rear Adm. R.W. Hayler, USN ComCriDiv 12 to ComServPac.) 3.

It is pointed out that the cruisers may be immobilized against a shore

background and become easy prey to subs penetrating the destroyer screen or

firing torpedoes from outside of it. A

very dark ship is therefore called for and if maximum danger comes only from

submarines would offer good concealment against shore, but it would be

unsatisfactory if the shore proved

to be thc greatest source of danger. Here

are two pertinent comments on the dark ship. "Dark

ships are bad all the time" Rear Adm. G.B. Davis, USN, ComBatDiv 8

(interview on U.S.S. INDIANA 8/19/44). "We

have found the darker ships easier to see at long ranges than lighter painted

camouflaged ones" Rear Adm. G.F. Bogan, USN, ComCarDiv 4 (interview on

U.S.S. BUNKER HILL 8/21/44). 4.

In addition to shore batteries the cruisers will have to expect torpedo plane

attack from the landward side. Comdr.

H.W. Seely, Gunnery Officer, U.S.S. WASHINGTON (interview of 8/17/44) said that

operations next to large islands will bring torpedo attacks usually from the

landward side since low flying aircraft can thus come in without radar

detection. 5.

Whether dark or light ships will be best appears to rest on the expected

tactical situation. We have no idea

how the pendulum will swing - perhaps nothing but one uniform color of paint

will be desired, but we believe we could provide better concealment wi1h pattern

designs of low contrast, and two tentative measure modifications, which we have

been considering, might be placed in the hands of the designers for experimental

work. I

Measure 33A colors: Light Gray (5-L) Haze Gray (5-H) II

Measure 31A colors: Haze Gray (5-H) Ocean Gray (5-0) Navy Blue (5-N) 6.

In both cases the designs should avoid sharp angular forms which are so useful

in deception and employ instead the more flowing contours appropriate for

concealment patterns. Some

deception may be retained if deception patterns of proven worth are used as

original starting points and remodelled into concealment patterns.

It will be noted that the colors do not include the extreme contrasts of

Pale Gray and Black normally found in these measures.

|